I recently finished the Disney CEO Bob Iger’s book which was pretty good. The most interesting parts of the book were his stories about Disney’s big acquisitions. Disney swallowed up Pixar, Lucas Films, and Marvel Studios under his leadership.

It even came close to buying Twitter, until Iger got cold feet and worried about the integration difficulties of merging such different companies.

This got me thinking of an experience I had with an acquisition several years ago. I was working as a data analyst at a small-cap, publicly traded tech company, in the ballpark of 500 employees and $300M in revenue. We provided tech solutions to big CPG clients and retailers. We’ll call it Company A.

A few months into my time at Company A, we acquired Company B for a relatively small sum, somewhere around $6M. Company B was a startup in our sector that had some promising technology, good employees and had raised money from prestigious VCs. But it had struggled to scale and was low on cash and so we bought them in what was essentially a fire sale.

I was a relatively new analyst and was tasked with taking over the analytics workload from Company B. I was initially told it wasn’t a big project, it would be a week or so of work and then maybe an hour a month of upkeep. This of course turned out to be a vast underestimate.

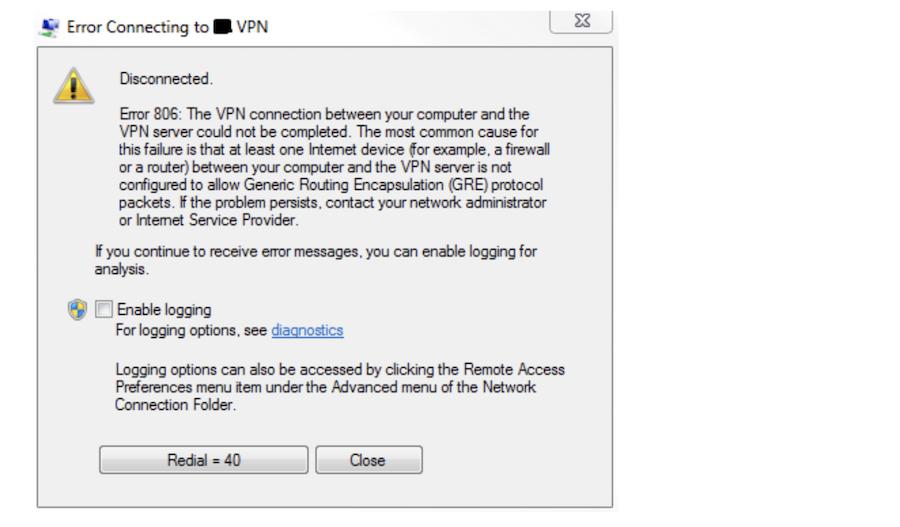

It is common knowledge that mergers can be messy and complicated but I had never experienced it firsthand. It was a great experience for me to see what the difficulties of integrating two companies actually look like. There were small difficulties (everyone needed to work off two separate VPNs for months) and bigger difficulties (clients of Company B had expectations that Company A couldn’t meet after the acquisition).

The following are some things I learned and some things I would do differently if I led an integration of data companies.

M&A is an ego-driven aspect of business

It seemed to stroke our CEO’s ego that he had the power to buy other companies. I think many people, especially those who self-select into business school and executive roles at companies, find it intoxicating to treat M&A like a game of Risk, moving pieces around a board with a high-level view of strategy.

Unfortunately, companies are made up of people who make up systems that are a lot more complex and harder to move and combine than Risk pieces are.

The acquisition process is emotionally turbulent, especially for the acquired company, and the effects of this turbulence were immediately apparent in our integration with Company B.

The acquiring company’s employees get this strange sense of superiority over the acquiree. It reminds me of the Stanford Prison Experiment. People are thrown into arbitrary roles where they were either given power or were powerless, and immediately took into their minds that they deserved it. Company A’s employees talked derisively about Company B’s strategy; Company B’s employees were immediately defensive.

In what was a relatively small-scale acquisition, there was still a lot of inefficiency driven by politics and emotions over who was responsible for what, finger-pointing when things went wrong, and anxiety over the future of the joint business.

Respect the acquired employees

This can go a long way in dealing with the aforementioned ego-driven conflict.

I tried to be very consciously kind to and respectful of Company B’s employees from the very beginning. If I were to go through this process again I would stress this idea more explicitly to people on my team. Being acquired is stressful; the employees’ work lives are thrown into flux and people deserve to be treated with respect.

In addition to being the right thing to do, developing a good relationship with Company B’s made the technical integration much smoother. As I was taking on Company B’s analytics systems, there were tons of snags and things I needed to learn, and Company B’s analytics employees were extremely helpful to me, when they really didn’t need to be. I think if I’d treated them like second-class citizens just because I happened to be working at a company that bough their company, my job would have been much more difficult and the merger would have been more costly.

A quick example of this: there was a monthly report that Company B ran for its biggest client each month. It was not technically complicated, but required knowing the the correct dates to use as filters in a SQL query to get the correct number of users who engaged with a product.

This wasn’t documented anywhere, and the analyst for Company B left the company shortly after the acquisition. It was only because one of the software engineers from Company B was willing to help me out that we were able to keep running this report for the client. He very easily could have blown me off; he worked remotely and this didn’t affect his job at all. It was only because I had a friendly relationship with him that this report didn’t slip through the cracks.

Have a specific person from the acquiring company in charge of the integration

There should be a clearly defined person in charge who is high-ranking at the acquiring company. There are lots of decisions that should be made early that are short-term painful (switching CRM systems, changing analytics workflows) but long-term necessary. There needs to be someone with the authority to make these decisions.

We cost ourselves several months of work because we didn’t make key decisions fast enough, since no one really knew who was in charge. Mergers are a time when explicit direction is necessary because there are a lot of tradeoffs inherent in integrating two systems, and it needs to be clear to the team what to optimize for when making these tradeoffs.

This person should also set expectations with external clients about what the relationship with the combined entity will look like after the integration, and what will change in the service they receive.

Use the merger as a time to rethink stale processes

Just because either company has done things a certain way does not mean that this is optimal, and a merger is a good opportunity to take a step back and re-work processes so that they’re more efficient and scaleable. This will take some development time and resources, which is why it’s so important to have a high-ranking employee of the acquiring company sponsoring the integration to provide cover.

As an example, Company B used an Excel template that was fed by a SQL script to do its standard analytic reporting. This worked okay for them at the scale they were operating at before they were acquired. But it quickly broke down when Company A started selling its products and the volume of requests tripled. Fully automating this reporting process took a few weeks of work but was entirely worth it and in retrospect we should have invested in doing that months before we did; it would have saved many hours of work and a lot of frustration.

The cost of integration is largely independent of acquisition price

Company A bought Company B for a few million dollars. But the cost of integrating them would have been essentially the same if they were a hot company that was doing very well and we had bought them for 80 million dollars. This is important to think about when considering cheap, “bolt-on” acquisitions. The cost of integration can really eat into the value accrued from the acquisition. I only have a view of the labor cost of our integrating Company B, but I’d be surprised if it was less than $1M.

Even similar data sets can be very difficult to integrate

Companies A & B had very similar data in terms of structure and quality. But it was still a nightmare to integrate our technical systems and processes, and I’m not sure that it ever was truly integrated (I left the company before that happened).

There were

- Legal issues around what data we could combine, what we could share with clients, and whether Company B’s data was properly anonymized

- New schemas and variable names for analysts to learn

- Reporting methods that Company B’s clients were used to and had been promised, but that didn’t make any sense for Company A to continue to deliver without a fee

- Different primary keys which made combining even otherwise identical datasets difficult

And a whole host of other issues. The point is that it’s very hard to foresee what these issues will be, especially for an executive who is three organizational layers removed from working with a database. This makes technical integrations really risky in my view, and if I ever lead one I will make sure someone who knows the database intimately is part of the diligence team.

Do your best to keep acquired employees

During our merger, many of Company B’s technical employees left. This is common during M&A transactions but amplifies the difficulty of combining systems because oftentimes the people with knowledge of why systems were built they way they were are gone.

It is very valuable to retain acquired employees, at least for a few months as the companies are being merged. I would be very generous in offering packages to these employees as they will be more valuable than any consultant you can hire to help with the integration.

Thanks for reading! If you have any experience with merging data companies I’d love to hear about them; reach out to me via email at [joe at this website] or on twitter.

If you like reading about this sort of thing, sign up below and I’ll email you when I write something new: